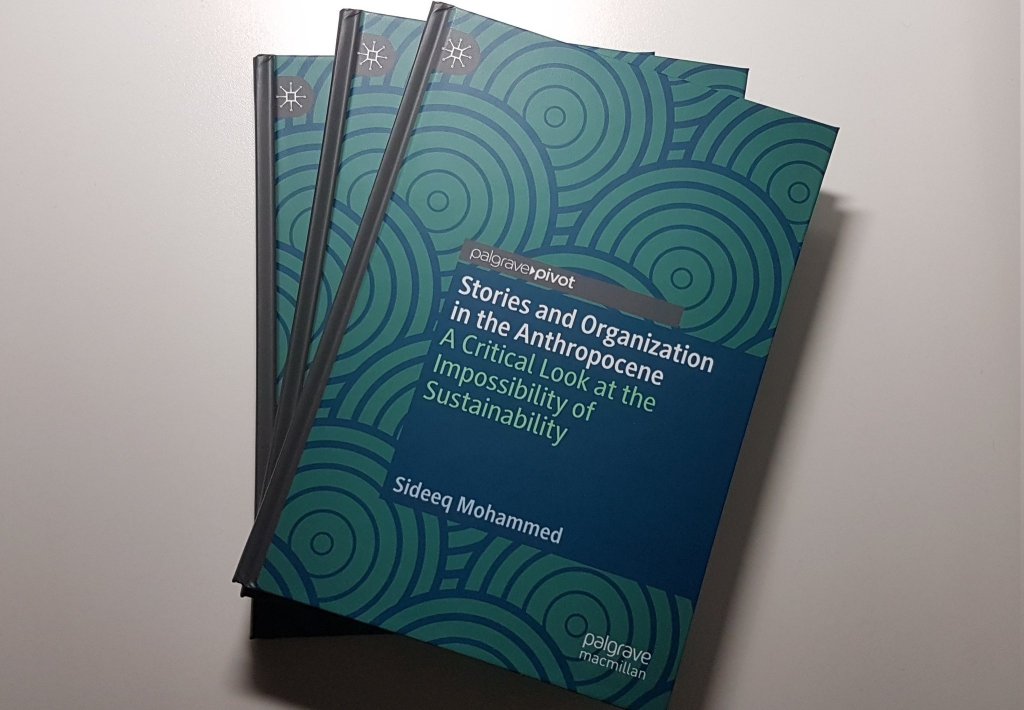

I’ve been asked to give a lecture on Research Ethics in a couple of weeks time and, as such, have been reviewing some of my old material on the matter. I came across the following essay and enjoyed reading it enough that I decided to post it here. I am aware that it is not without shortcomings (limited reading being prime among them) and that is largely reflective of the particular moment within my doctoral work which produced it, but I thought that its playfulness, its creativity and the references that it highlights were worth a second consideration.

Cultivating a Deleuzian Ethics of Ethnography: A Polemic

At no other point could we have suggested a Deleuzian ethics. Even now it seems impossible; teetering on the edge of absurdity. To suggest, therefore, a Deleuzian ethics within the context of an ethnography of the shopping centre is to make a move, both in terms of theory and practice, which plunges all of the multiple discourses at play in this field into utter disarray. This is to reach a limit and start writing nonsense or, more accurately, to begin to cultivate a mode of engagement and inscription that is preoccupied with the sensible and the immanent through both its nature and content. It is to revisit the question of ethics entirely, melding and scrutinizing theory and practice, in an attempt to understand how the discourse of ethics in ethnography has reached this particular point, an exploration that falls just shy of genealogy. In sum, this polemic will begin to trace the initial moves (and only these) of the horticulturist who seeks to develop an ethnography- one that is necessarily not homogeneous with such a descriptor- in conjunction with a reading of the works of Gilles Deleuze. Through taking risks and making disjunctures at points, through examining current anthropological literature which relates to the focused frame of “engagement and ethics”, we shall attempt the cultivation of a Deleuzian ethics of ethnography.

Adam…

Adam was the first ethnographer. He is placed into the Garden with no assumptions or presuppositions and he begins to name his research subjects, the others, the anonymos; indoctrinating them into his language while learning theirs and studying the ways in which these others relate to one another. He names them, even though he knows that they may have their own names; that they may have already named themselves and each other. He does so without morality because he has not yet eaten of the tree of knowledge of good and evil. However, he still has an understanding of how to engage with and relate to the others in the garden. One might say that this understanding comes from the fact that he labours under the tyranny and in fear of an omnipresent and absolute Other, which is why he does not partake of the fruit of the tree. For Deleuze, this is indeed the case, but mistakenly so. Adam does not eat because he believes that god prohibits it. He is mistaken because he cannot understand that god has merely revealed the natural consequence of eating of the fruit of the tree: an adverse reaction between bodies; poisoning. Though he does not know it, Adam acts based on his sense of the interrelations of bodies; his comprehension of conjunctions and disjunctions. He is, for the moment, beyond good and evil. His ethics are immanent.

An exercise in ‘box-ticking’…

Immanent ethics are, however, unfortunately far removed from current discussions of ethics in anthropology. What can and should be termed the ‘administrative approach’ to ethics is what presently forms common parlance; the everyday reality of ethics as far as social scientific research is concerned. The complexity of the myriad problems concerning how one is to relate, regard and engage with others in the world has, of late, been reduced to an exercise in box-ticking in order to facilitate committee approval. “Does the research involve any of the following? Please tick where applicable.” “Provide a summary of the design and methodology of the project, including the methods of data collection and the methods of data analysis.” This is what Michael Agar (1980) would describe as ‘the bureaucratization of ethics’; a result of escalating fears regarding the treatment of ‘human subjects’ within a research context. While it might appear that ethical approval procedures have evolved from the time when Agar wrote his text, or indeed, from when authors like Wax (1977) critiqued similar approaches to ethics that governed research in the social sciences, closer examination of the works of more current authors, like van den Hoonaarud (2001, 2003), reveals the articulation of similar discontent with current systems. In sum, what these writers argue is that, though a degree of bureaucratic oversight might prove necessary, these approaches reduce ethics to a series of steps necessary, in the first place, for the maintenance of a minimal standard that will shield both the researcher and their institution from the perils of legal inquest and, secondly, to patronizingly guarantee the informed consent, confidentiality and the security of any ‘human subjects’ under study.

It is possible to understand these bureaucratic measures as emerging based on a broadly natural-scientific model of research; one where methods are more rigidly defined and adhered to, where the interactions between researcher and ‘subject’ are much more controlled and where power relations are better established (even entrenched). Indeed, most accounts of the historical emergence of “research ethics” (see, for example Hesse-Biber and Leavy, 2011) begin with the Nuremberg Code and a recounting of the medical experimentation that preceded it. As such, it is not difficult to see these procedures as an external code of practice which has been imposed upon the social sciences despite the fact that the specificity of such codes does not lend itself to the ‘inexactness’ of qualitative research methods in general and the emergent nature of ethnographic fieldwork in particular. Were it not for infamous social scientific research like Zimbardo’s (1973) ‘Stanford Prison Experiment’ or Humphrey’s (1970) Tearoom Trade, it would be possible to argue that the social sciences have no need for such ethics of committees and procedures. We do not here place blame, but merely point out that, regardless of whether the methods employed in these ‘experiments’ were necessary or not, they undoubtedly catalysed the emergence of the prescriptive and restrictive ethical procedures which now govern (read: mediate) engagements with ‘human subjects’, supposedly for the protection of vulnerable subjects and researchers alike. As such, while more systemic and social origins can be isolated- van den Hoonaarud (2000), for example, posits the emergence of a kind of ‘moral panic’, a by-product of modernity which exaggerates perceptions of harm and results in disproportionate regulation- this administrative approach to ethics is clearly one that the social sciences, and we as social scientific researchers, are complicit in constructing.

Still, the scope of the administration of ethics cannot but be shocking and yet, writing based on his time spent on a Canadian Research Ethics Board, Haggerty (2004) not only demonstrates that this phenomenon is global and endemic to the entirety of social science but that it is one which is growing. He chronicles a phenomenon that he dubs “ethics creep”, the growth and evolution of bureaucratic procedures and committee oversight for conducting social scientific research, and goes on to argue that this phenomenon is largely detrimental to the overall ethical conduct of the social scientific field, encouraging rule fetishization and the neglect of ‘true’ ethical engagement with others in the field (a point that we shall consider further below). Indeed, though its openness should render it as an exceptional case, the spread of administrative ethics permeates all the way to the field of anthropology, manifesting, for example, on the pages of the ethical guidelines published by professional associations like the Association of Social Anthropologists (ASA). The ASA’s ethical guidelines bear the distinct marks of having been revised to take into consideration certain ethical quandaries and problems with ethical practice that have troubled ethnographers in years past. Yet, like all other such ethical mandates, it functions along the axes of the problem of informed consent, the nature of ‘harm’ and the guarantee of anonymity; each of which we shall consider in further detail because, as can be learned from Murray et al (2012), it is positioning along these three axes that becomes crucial for obtaining ethical approval when conducting social scientific research. By implication, one must not only understand them in order to act ethically but in order to ‘get the box ticked’ and be allowed to carry out one’s ethnographic particular project.

Problematic Axes

On the surface, the premise of informed consent seems fair, necessary and unproblematic. That the subject under research should know and understand the nature of the research endeavour and be asked to acquiesce their participation in it before it begins, seems to be not only a reasonable and ethical mode of conduct but it also seems an effective way to placate any fears of the exploitation of marginal or otherwise vulnerable social groups. Several researchers have, however, called into question the whether informed consent is possible in ethnographic projects, whether the researched can ever truly give an informed and un-coerced ‘yes’.

In her exploration of this particular problematic, for example, O’Connell Davidson (2008) comments on the seeming vacuity or ambiguity of the consent that ethnographers are mandated to secure at the beginning of the fieldwork. Through a retrospective of her relationship with her informant, Desiree, she questions whether saying ‘yes’, acquiescing to the requests of the ethnographer, can really be considered as consent, given that neither the ‘human subject’ under study, nor the researcher knows how their relationship will evolve. To wit, since neither party is aware of how the subject’s life will be portrayed and dissected in the text that results from the fieldwork or, indeed, what aspects of the interaction will be featured in such a text; how can the subject ever meaningfully say ‘yes’. Here the spectre of the natural scientific/medical origins of the practice of securing consent looms large, as these problems are exacerbated if we consider consent as processual, a continually negotiated position (which it is for most ethnographic projects), rather than a singular and one-time ‘yes’, signed on a dotted line. That is, if we consider ethics as something more than an administrative exercise, the entire idea of informed consent becomes fallacious. What is being called into question here is both the ethnographer’s ability to ‘inform’ the ‘human subject’ under research, to tell them what the research is before the fact, as well as the subject’s ability to understand such a description; problems which cannot be so easily dismissed.

Further practical considerations are raised by Haggerty (2004) and others, such as the ability of the ethnographer in the field to secure consent from casual encounters in public spaces. Indeed, if our ethnography is to involve working at the Lost and Found desk in the shopping centre, this particular problem of securing informed consent becomes most troubling. The casual shopper who comes up to the desk to ask for directions, the beleaguered mother-of-three who comes in search of a mislaid diaper-bag, the janitor who stops to say ‘Hello’ during his 3pm rounds of the ground floor- none of these may be presented with a waiver, a statement of ethical intent or interrupted in their conversation by a lengthy explanation of purpose and nature of our particular ethnographic project. To do so is at best, impractical, and at worst, detrimental to the ethnography and its goals. Such encounters are, however, vital; not only for the ethnographer to assimilate himself into the community but for the development of an understanding of the space, in every aspect of the word. Should we shy away from such encounters in fear of some ‘harm’ that we might inadvertently cause or unpragmatically adhere to the doctrine of informed consent?

Equally problematic and fraught with controversy is the question of anonymity and confidentiality; terms which are by no means synonymous but both of which indicate a certain imperative to protect the identities of the ‘human subjects’ under research. Even though it is more likely that the practice of guaranteeing anonymity and confidentiality emerged in order to secure the cooperation of certain reticent research subjects, one can see how such a practice might be necessary to safeguard vulnerable individuals and groups; protecting them from any potential repercussions from their appearance in the ethnographic narrative. It seems clear that this should easily manifest in the usage of pseudonyms, the obfuscation of distinguishing characteristics of people and places and the non-disclosure of information which is deemed to be sensitive. What has been called into question in recent anthropological literature, however, is whether or not these practices offer any meaningful form of protection.

As Arlene Stein (2010) notes in a recounting of her ethnography of ‘Timbertown’, the town’s residents were easily able to discern the identities of the individuals featured in her text The Stranger Next Door, despite her attempts to give them anonymity. Her descriptions and depictions, being necessarily detailed for the construction of an ethnographically-informed narrative, were easily decipherable because of the small size of the community under survey. Among the conclusions of her retrospective, she asserts that it was perhaps the very promise of anonymity- a promise which would not have been made by an investigative journalist pursuing the same line of inquiry- that caused so much ire in the wake of her book’s publication. That is to say, having been promised anonymity, her informants felt that they had been outed, their trust violated by the researcher’s faltering attempt to mask their identities. Stein, therefore, concurs with Nancy Scheper-Hughes who, in writing about a similar situation in which her disguised field-site was unveiled, asserts that the “time-honoured practice of bestowing anonymity on ‘our’ communities and informants fools few and protects no one—save perhaps the anthropologist’s own skin.” (2000, p. 128).

Indeed, we are likely to face a similar problem to Stein and Scheper-Hughes in the shopping centre, which we must assume is populated by a relatively small community of staff. No matter what pseudonym we use or how we disguise our description of the site, the staff of the shopping centre will know that they are the ones being written about and will very likely be able to decode even the most veiled depictions of individual subjects. Do we deny their right to anonymity and hope that they will still speak to us or do we offer only the most transient sham of anonymity in order to satisfy administrators and ethics committees? Or, do we obscure all of an individual’s distinguishing features (including their race, gender, socio-cultural affiliations and position in the organization), ‘protecting’ them at the cost of producing a weak and unpersuasive ethnographic narrative that ignores the importance of positionality? It is regrettably the case that the latter two options are selected far more frequently than the first. It is for this and other reasons that van den Hoonaarud (2003) suggests that, while it may be more easily deployed in quantitative methodologies, true anonymity is an impossibility as far as ethnographic research is concerned. We are inclined to agree, given the potential difficulties to which we have alluded; even if this would seem to render the ‘human subjects’ in our ethnography vulnerable to ‘harm’.

Indeed, the third and final axis, ‘prevention of harm’, the one which the other two exist to serve, is disputable for precisely the reasons which we have been outlining. To return to the ASA’s ethical guidelines, the anthropologist is charged to anticipate and minimize ‘harm’, to mitigate any foreseeable negative consequences to the ethnographic project. This might take the form of reassuring the directors of the shopping centre that no confidential, sensitive or potentially harmful information regarding the organization and its practices would be disclosed; having recourse to a councillor if the project involves the reliving of painful memories in response to an ethnographer’s probing questions (Murray et al, 2012) or, more simply, anonymizing the names of participants who aren’t openly gay to keep from outing them (Stein, 2010). The problem which is highlighted by the examples that we have entertained thus far is that it is the unforeseeable, the unpredictable, that tends to be the most damaging, that causes the most harm. Equally, however, it is this unpredictability that makes ethnography a useful and indispensable methodology. How does one, therefore, proceed without harming the ‘human subjects’?

In his paper on the moral dilemmas of fieldwork, the Ten Lies of Ethnography, Fine (1993) describes the shared delusions that ethnographers present to the world (and to each other), key among them being the lie or myth of “the honest ethnographer”- one who always secures consent, anonymizes his informants and always knows exactly what he is looking for in the field. While we concur, we would also argue that what Fine is unable to postulate is a more endemic cause, a capitulation that encourages the fieldworker to tolerate the now obviously vast disjuncture between the administrative approach to ethics and those that must necessarily exist between the researcher and the ‘subject’. What we suggest is that the problems that emerge with regard to ethics and fieldwork- particularly those which we have catalogued thus far- stem from the transeunt or transcendental approach to ethics that pervades in social science and indeed, in wider society. It is the tree of knowledge (paradoxically comprised of axes) which we have been administered, and by which we are administered (always complicit in its construction), that seems to be the root of these problems. It is when he or she feels that they must labour in the shade and under the gaze of this omnipresent other- the ethical guidelines and contradictions internalized- that the ethnographer feels alienated, uncertain, and indeed, impotent, and so questions (as we are doing) the ethical framework that has been put upon him. To understand the alternatives that are available to researchers, and indeed, to ‘human subjects’ in the course of their everyday lives, we must engage in a closer interrogation of Deleuze’s ethical project.

Encounters…

Encounters between Deleuze and ethnographers are limited and fleeting when they do occur. Perhaps this is because, as Biehl and Locke (2010) so aptly demonstrate with their misappropriation of many of Deleuze’s concepts (most notably ‘desire’ which they mistake for sexual desire via Freud), the onto-epistemological assumptions that simultaneously govern and underpin anthropology, and indeed ethics in anthropology, are ostensibly incompatible with any philosophical approach that might be termed ‘Deleuzian’. There would appear to be no reconciling the vestiges of the scientific method and progressivism that form a core of anthropological discourse (see Adams 1998); vestiges that result in Biehl and Locke’s attempt to cultivate a ‘Deleuzian anthropology of Becoming’ amounting to little more than an ex post facto imposition of Deleuzian terminology onto a completed ethnographic project. Their engagement with concepts like ‘becoming’ or Deleuze’s understanding of writing cannot disguise their continuous employment of phenomenological metaphors or hide their psychoanalytically informed preoccupations with pathologies and cures; so much so that they act unethically (for a schizoanalyst), botching the becoming-cat of their informant, Catarina.

This seeming irreconcilability does not derail our present endeavour since we maintain that there are ways, becomings, via which a Deleuzian may engage with and in ethnographic practice. This polemic, however, is not and cannot be directed at such a systemic problem. For now it will have to be sufficient for us to draw attention to this conflict and posit, with an attentive ear towards ethics, that the difficulties in developing a Deleuzian approach to ethnographic or anthropological methods stem from the fact that there is no Deleuzian tree of knowledge from which the Adam-ethnographer can pluck the fruit of ethics. Such ethics must emerge inside, in-between and through engagements; growing rhizomatically. Perhaps the most productive attempts at developing a Deleuzian ethics within the context of an ethnographic fieldwork project comes from authors who understand this.

In FoodScapes, a text which addresses itself to developing a ‘Deleuzian ethics of consumption’ through a multi-site ethnography, Rick Dolphijn (2004) demonstrates such an understanding. Much like Smith (2007), Dolphijn picks up on the distinction which Deleuze draws between ‘ethics’ and ‘morality’ in his text on Spinoza– a distinction which is reprehensibly absent from the administrative approach to ethics. Via Spinoza’s Ethics as well as Nietzsche’s Genealogy of Morals, Deleuze understands ‘morality’ as referring to systems of transcendental values or prior judgements, philosophies of ‘good’ and ‘evil’ that pre-exist the event or assume a position of exteriority to the engagements of the encounter. It is such ‘moral philosophies’ that we have alluded to as being the source of discontent within anthropological theory, since it is these, in their totalizing and rigidifying modes, which come to delimit individual action and restrict the varying range of engagements between bodies that may occur during ethnographic fieldwork. Morality is here a mechanism of constraint, control and organization; one which we must understand, through Nietzsche, as the product of specific power relations and practices. To paraphrase Twilight of the Idols, the researcher must set himself beyond this, recognizing such illusions to be beneath him. Indeed, for Deleuze, great moral thinkers like Bentham, Mill and perhaps even Kant were inherently unethical as, in their construction of totalizing and prescriptive moral frameworks, they regulate and restrict the possibility for ethical engagement. Only etiolated ethics can result from such approaches. As such, it would seem apropos to retroactively redub the term ‘administrative ethics’, changing it to ‘administrative morality’- a given morality that the ethnographer bears as a rite de passage, a necessary evil for a greater good, a crutch, an anaesthetic that dulls the thorny feel of the engagement.

The term ‘ethics’, on the other hand, is one which is employed in reference to “a typology of immanent modes of existence” (Deleuze, 1988. p. 23), to a system of understanding (one that borders on a set of rules) that encompasses the constitution of bodies and the way that these are composed and decomposed within the event. For Adam, the fruit of the tree would poison him, decomposing his body; the fruit, by virtue of its very composition, being antagonistic to his nature. He understands this to be a negative form of engagement, ‘bad’ one might say, and shies away from it until he is convinced that the fruit is, in fact, nourishing- a positive engagement between bodies. He acts neither upon the realization that ‘poison’- as we know via the history of medicine and language encapsulated by the etymological roots of the word pharmakon– is contextual and is only a meaningful term within a given assemblage nor upon a transcendental imperative (in fact, the story tells us that he is innocent of these) but on an immanent ethology. It is this that Dolphijn focuses on in FoodScapes, “the compositions of relations or capacities between different things” (Deleuze, 1988. p. 126), the relations, processes, reactions and functions of food that emerge from the different field sites in his study.

The truly ethical question, therefore, is not “What must I do?” or how best can I perpetuate and persist in my subordination to this illusionary transcendence, this imposed moral code of conduct? Rather it is “What can I do?”- what possibilities are available to me as a researcher and to the other subjects within a given assemblage? What becomes in these? Ethics are here facilitative rather than prohibitive. In fact, while one is still surf to morality, still preoccupied by issues of consent and anonymity, of ‘good’ and ‘evil’, we neglect the ethical questions of engagements. Ethics is itself prohibited since transcendence disbars ethical action.

Departing the Arboretum

The question which still haunts us, is whether Adam acted morally in the Garden? Did he consider the potential sources of harm and attempt to mitigate these? When he names the animals, is he actually anonymizing them to protect them from some hitherto unmentioned harm or is he robbing them of their names, giving them new identities and keeping their story out of history? It seems to us that the lesson to be learned from Adam is that ethnography can be amoral. It is rarely unethical, but it can (and perhaps should) take place in the absence of a rigidly defined moral structure.

Upon reconsidering the questions raised in the preceding sections, it is clear to us that many of these must remain unanswered at the present juncture since, in our own ethnographic project, we have not yet encountered the others, any other actual bodies, and do not yet know whether anonymity, consent or harm will be involved in our ethical mode of relating to them. This is not merely a situational or relativistic proposition which says that we will subscribe to the administered morality where it is suitable, but rather, it is one that says that we should cease to be preoccupied with such a code; it is restrictive and universally inapplicable; focusing instead upon the ways and means by which we engage with the others in the field, an ethics more indicative of practice.

Indeed, retrospecting further, the Deleuzian ethics which we have been considering can produce new offshoots/readings of some of the ethical quandaries in anthropology. Humphrey’s Tearoom Trade, for example, was immoral by the standards with we have defined but it was certainly not unethical. In the case of the becomings of Biehl and Locke, their research was unethical not immoral. Ethical conduct would have been learning to speak to Catarina in her own language; leaving her to her becomings; helping her understand her coding, her lines, the territories through which she has passed and is passing as well as the forces at work upon her desires and how these arose- not delivering her into further repression by trying to find the ‘true nature’ of her “rheumatism”. Such ethical conduct would not have merely been between Biehl and Catarina but between Biehl, Locke and Deleuze; an ethical mode of engaging with a body of literature, one that we hope to employ in our own research.

It would seem, therefore, that there is still much more growing to be done.

Bibliography

Adams, W. Y., 1998. The Philosophical Roots of Anthropology. Stanford, CA.: CSLI Publishings.

Agar, M. H., 1980. The Professional Stranger: An Informal Introduction to Ethnography. London: Academic Press Ltd. .

Biehl, J. & Locke, P., 2010. Deleuze and the Anthropology of Becoming. Current Anthropology, 51(3), pp. 317-351.

Bogue, R., 2007. Deleuze’s Way: Essays in Transverse Ethics and Aesthetics. Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

Association of Social Anthropologists of the UK and Commonwealth, 1999. Ethical Guidelines for Good Research Practice. [Online] Available at: http://www.theasa.org/ethics/guidelines.shtml

[Accessed 29 December 2012].

Davidson, J. O., 2008. If no means no, does yes mean yes? Consenting to research intimacies. History of the Human Sciences, 21(4), pp. 49-67.

Deleuze, G., 1988. Spinoza: Practical Philosophy. San Francisco: City Lights Books.

Deleuze, G., 1997. Essays Critical and Clinical. Minnesota: The University of Minnesota Press.

Deleuze, G., 2001. Pure Immanence: Essays on A Life. New York: Zone Books.

Deleuze, G. & Felix, G., 2010. A Thousand Plateaus: Capatilism and Schozophrenia. London: Continuum.

Dolphijn, R., 2004. Foodscapes: Towards a Deleuzian Ethics of Consumption. Delft: Eburon.

Fine, G. A., 1993. Ten Lies of Ethnography: Moral Dilemmas of Field Research. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 22(3), pp. 267-294.

Haggerty, K. D., 2004. Ethics Creep: Governing Social Science Research in the Name of Ethics. Qualitatitive Sociology, 27(4), pp. 391-414.

Hammersley, M. & Atkinson, P., 2007. Ethnography: Principles in Practice. London: Routledge.

Hesse-Bieber, S. N. & Leavy, P., 2005. The Ethics of Social Research. In: The Practice of Qualitatitive Research. London: Sage Publications, pp. 83-116.

Humphreys, l., 1970. Tearoom Trade: A study of homosexual encounters in Public Places. London: Duckworth.

Jun, N. & Smith, D. W., 2011. Deleuze and Ethics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Murray, L., Pushor, D. & Renihan, P., 2012. Reflections on the Ethics-Approval Process. Qualitative Inquiry, 18(1), pp. 43-54.

Nietzsche, F., 1990. Twilight of the idols and The Anti-Christ. Harmondsworth : Penguin .

Nietzsche, F., 1996. On the Genealogy of Morals. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Raymond, M., 2010. Being Ethnographic: A Guide to the Theory and Practice of Ethnography. London: Sage Publications.

Scheper-Hughes, N., 2000. Ire in Ireland. Ethnography, 1(1), pp. 117-140.

Smith, D. W., 2007. Deleuze and the Question of Desire: Toward an Immanent Theory of Ethics. Parrhesia, 2(1), pp. 66-78.

Stein, A., 2010. Sex, Truths, and Audiotape: Anonymity and the Ethics of Exposure in Public Ethnography. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 39(5), pp. 554-568.

van den Hoonaard, W. C., 2001. Is Research-Ethics Review a Moral Panic?. Canadian Review of Sociology, 38(1), pp. 19-36.

van den Hoonaard, W. C., 2003. Is Anonymity an Artifact in Ethnographic Research?. Journal of Academic Ethics, 1(1), pp. 141-151.

Wax, M. L., 1977. On Fieldworkers and those Exposed to Fieldwork. Human Organization, 36(1), pp. 400-407.

Zimbardo, P. G., 1973. On the ethics of intervention in human psychological research: With special reference to the Stanford Prison Experiment. Cognition, 2(1), pp. 243-256.

Thanks must go to Dr. Stef Jansen whose course on Issues in Ethnographic Research catalysed and nurtured this essay.