Perhaps one of the hardest things in the world to accept is that other people might consider the same information as we do and arrive at different conclusions. Most of us are so sure of the efficacy of our thought processes that it may not ever occur to us that they may be flawed or problematic. This is a less lucid and self-aware reflection than it seems to be, because I am here simply trying to think about how it is possible for anyone to still believe that “ethical capitalism” is possible. I have taken to openly saying to students and colleagues that “anyone who seriously believes in the possibility of a contemporary corporation acting with genuine ethical concern is either dangerously delusional or an irretrievable idiot; I don’t know which is worse.” This never fails to be a divisive comment – not only because it is very heavy-handed but also because it plays fast and loose with the term “ethics”, so I wanted to offer a clarification. Without a digression into contemporary moral philosophy (which I am not well-read enough to sustain), an “ethical capitalism” – as most would understand it – would be a form of capitalism that seeks not only the increase of private wealth but also places value on human and social well-being. This is an impossibility. Here’s Peter Bisanz writing for the World Economic Forum, which I quote at length because it is important:

“Call it what you like: conscious capitalism, responsible capitalism, ethical capitalism – the better way to practice capitalism is to move the needle towards creating long-term socio-economic and environmental value: a business model with a higher purpose, where businesses build deep, trust-based relationships with their customers, employees, suppliers, investors and society. The bottom line benefits too from this kind of ethical, values-driven capitalism. Businesses adopting this model attract more customers, reduce operating costs through energy efficiency and lower waste, boost employee loyalty and enjoy engaged workforces that share the corporate vision, aspirations and goals.”

The paradox here should be obvious but isn’t is this is a popular refrain within many academic circles – “being ethical is profitable”. The logic of wanting a business model with “a higher purpose” and wanting a business to continue to maximize the benefits to their bottom line is never considered as mutually contradictory or fundamentally in conflict. The axioms of contemporary capitalism – perpetual growth, assimilation of paradox, market sovereignty and so on – make it impossible to even conceptualize a reality wherein a business may have to make a loss to serve a higher purpose (as an aside, this is why I’ve been so fascinated by the reaction to Jeremy Hunt’s comments about a no-deal Brexit, precisely because they break this taboo and blaspheme against the market). In this sense capitalism has an “ethic”: accumulation. Capital seeks only to grow, through whatever combinations and conjunctions it can make.

I read about my new favourite examples of this on the train to EGOS in Edinburgh. Here’s Bloomberg’s Peter Robinson reporting on the Boeing 737 debacle:

“The Max software — plagued by issues that could keep the planes grounded months longer after U.S. regulators this week revealed a new flaw — was developed at a time Boeing was laying off experienced engineers and pressing suppliers to cut costs.”

What recent reporting has brought to light is that increasingly, the iconic American plane-maker and its subcontractors have relied on temporary workers making as little as $9 an hour to develop and test software, often from countries lacking a deep background in aerospace development. While the entire story of the 737’s development, reads like an attempt to prove that only economic interests, as they pertain to wealth accumulation, are represented in decision making, it is this outsourcing – the kind of story that seems too moronic not to be true – that highlights what happens when the profit motive clashes with any other concern (in this case valuing human life). Profitability wins, every time. This case doesn’t really tell us anything about the blood-soaked calculus of economic rationality that the Ford Pinto case didn’t tell us in the 1970’s; laying off your experienced software engineers, and outsourcing their work to a cheaper organization in the global South and possibly directly contributing to the deaths of hundreds of people, was very likely the most profitable option, even considering the $100m payout that is supposed to go to the families of the 346 people killed by the 737 crashes. Yet one can go to Boeing’s websites and read about their social responsibility policies and how much they invest in “communities”. And if I asked my undergraduate management students, “Is Boeing an ethical company?” it is from this very page that they would quote in order to tell me that it is.

Yet, since the 1990’s, public intellectuals like Noam Chomsky have been commenting on the ways that companies like Boeing are gaming the system and using military investment to further their interests. We have long known that companies like these represent a perfection of the capitalist logic of perfidious accumulation, using any means necessary to grow and agglomerate wealth, while an entire social and political apparatus convinces us that this is merely the disembodied will of “the market”. Here “management” as a practice is itself unveiled as entangled – the decision taken on a microlevel to cut costs through layoffs and outsourcing is inextricable from the regarding of “the market” as sovereign and the profit motive as the only true and legitimate impetus to action – producing the predictable effect of people dying. This is to say nothing of the fact that we know how damaging flying is to the environment, meaning that Boeing’s profitability as a company fundamentally relies on us continuing to disregard the dangers of anthropogenic climate change.

I imagine that defenders of capitalism would say that its current predicament is the price that Boeing pays for not acting “towards creating long-term socio-economic and environmental value”. Yet we have to ask which of the axioms of capitalism Boeing is in breach of here? Is the shift in employment relations towards precarity and temporary working as evidenced by the much praised gig-economy not symptomatic of precisely the decision to seek out cheaper labour internationally? When we collectively know that we need to recycle to keep plastic out of our oceans but multiple journalistic exposes tell us that often plastic now goes unrecycled (destined for landfills or incinerators) because there’s no demand for recycling “due to poor market conditions” is this not the same logic of economic valuation privileged over everything else?

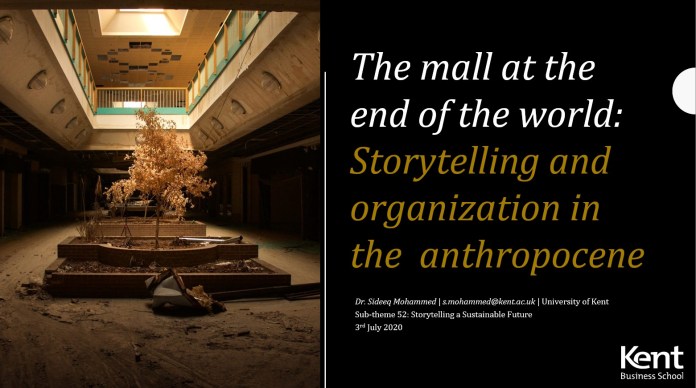

Getting reading to present a paper or desire, death, capitalism and the Anthropocene

I thought about this while attending a stream on Critical Organizational Anthropocene Studies. As I heard about the very ethical and environmental things that different organizations were doing, I thought about the character Waj, from Chris Morris’s incredible film Four Lions. Waj is characterized as a well-meaning but simple man whose defining character trait is perhaps that he consistently defers decision making (and thus ethical responsibility) to his presumably more ethical and intelligent friends. The deferral of ethical judgement to an other, allowing for a reality in which one could do or condone the doing of potentially horrible things is encapsulated in what I might stylize as a refrain of the question: “Is well ethical, innit bro?”. Perhaps it evidences that I have watched the film too many times but I can hear actor Kayvan Novak saying it in Waj’s accent and could hear it at times during colleagues’ presentations at EGOS.

Indeed, though I was participating in a stream on “Critical Organizational Anthropocene Studies” not many of the presentations treated seriously the question of what a “critical” study of organizational responses to the Anthropocene might be. Many of the presentations had a hopeful tenor, or one that we might recognize as a kind of business-as-usual for capitalism – turning any form of critique or revolutionary action into something in the service of its own end – and could thus be read as complicit in mobilizing environmentalism as a vehicle by which to “save” and preserve the mores of capitalism itself. Here’s a company in the circular economy that’s recycling concrete or turning fish scales into bioplastics, or here’s one that is taking seriously the “slow food” movement and building up a community concerned with sustainable, local, everyday practices, or here’s a co-operative volunteering to sort and recycle other people’s waste, or here are some people in the global-South involved in a recycling cooperative. Is well ethical, innit bro? I at times found myself envying the optimism of my colleagues – as well as admiring their passion for their work – but I find myself to be too cynical to be hopeful that these kinds of engagements as they seek to preserve the essential logics of capitalism by merely wrapping them in a “green” casing. Indeed, in the cruellest reading these organizations and their ethical/sustainable/circular economy moves merely function to allow capitalism to continue. But one can’t observe this, it’s too bleak, too uncomfortable a thought because of how roughly it grates against our fondness for the world that capitalism has built for us and how much it jars with the accepted mores of neoliberal subjectivity. “By trying to help you and champion those who you see as trying to bring about a better way, you may be making things worse; the main thing that you’re doing is making yourself feel better. There is nothing else that you can do.” I have to keep thinking about this, not just because it’s important but because it speaks to one of the defining features of contemporary capitalism, the assimilation of critique or its absolute reliance upon those who hate it.

What troubles me is that these kinds of arguments have been around for a while. Based on a decade long case study Wright and Nyberg’s (2016) An Inconvenient Truth: How Organizations Translate Climate Change into Business as Usual basically points out all of the same critiques that I might. That organizations’ short-term focus, focus and preoccupation with growth and revenue maximization make them ill-equipped to lead the fight against climate change. Most often we see organizations viewing the Anthropocene as an opportunity, seeking to profiteer off of it by providing the next new “sustainable” innovation. This was clearly put across by Andrew Hoffman in the context of a sub-plenary discussion on the Anthropocene when he said simply: “this is a great opportunity.” It was not immediately clear whether he meant that it was a great opportunity to further one’s academic career by publishing on the newest fad or whether he meant that it was a great opportunity for businesses to capitalize on a fast growing and profitable new sector but he later clarified by saying (overtly seeking to contradict Naomi Klein), and I quote:

“The market is the most powerful force on the planet. If business does not solve it [the problems of the Anthropocene], it will not be solved.”

The only way that we’ll see change in how organizations respond to the Anthropocene, according to a leading commentator, is via the logics of the market in a kind of eco-modernist optimism (presumably a demand for there not to be an ecological crisis will eventually be matched by a supply of “not an ecological crisis” once the time-lag is over). The role of an organizational scholar is therefore supposedly to show businesses how much money they stand to make if they start taking the Anthropocene seriously. It’s hard not to hear a simple abdication of responsibility to the other of “the market”. Is well ethical, innit bro?