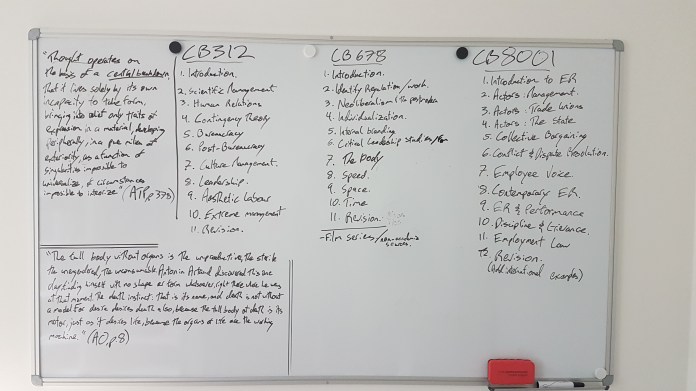

I haven’t really had time to update this blog over the last few months. Contemporary academia being what it is means that the reason for my hiatus is fairly predictable: three new modules. The first-year undergraduate, Introduction to Management module, was easy enough because I had other staff to help me manage the 450 students that I was trying to teach, and the final-year undergraduate Contemporary Management Challenges module was basically a Critical Management Studies module so I was (for once) teaching content that was close to my own work. I even spoke about Deleuze and Guattari in a few lectures which I enjoyed more than I should have. We will not speak about how my Msc Employment Relations module went because it’s over now and I still feel like I don’t know enough to teach it…

My rather crowded whiteboard.

Three modules isn’t really a huge workload; other colleagues have similar teaching responsibilities, but my research-intensive teaching style meant that I was easily working (teaching seminars, replying to emails, attending meetings, writing lectures, reading and annotating papers for classes, marking assignments etc.) for 12-13 hours every day, seven days a week, since the start of 2019. I am well aware that that is both absurd and double the number of hours that I get paid to work. Now that it’s over, I wanted to take some time to reflect on the experience. I picked out four themes that I think characterize the last few months: subversion, silence, scepticism, and self-destruction.

Subversion

In A Thousand Plateaus, Deleuze and Guattari tell us that “everything is political, but every politics is simultaneously a macropolitics and a micropolitics.” (p.213) They suggest that the politics of the state and the politics that we produce in relating to each other in the everyday are inextricably related. A fascistic state apparatus, for example, is inseparable from the ways in which we speak to, think about, and engage with each other in the course of everyday life (and vice versa). Despite this, I have never significantly invested in what might be termed “micropolitical acts of resistance”. The term is currently popular in Organization Studies and speaks to little things that we might do in the course of everyday life to disrupt, disorder, or destroy systems of control, discipline, and organization. For example, cause trouble by screwing up a performance appraisal form (and wasting organizational time in the process) that you don’t think that you should have to fill in because the contemporary obsession with maximizing performance is toxic and dangerous. There are many better explanations and examples of this because it fills organizational scholars with some odd sense of hope to know that while we they might not be able to effect large scale change in organizations, they can encourage, highlight, and give a platform to small acts of resistance. I am unsurprisingly cynical about this, not because micropolitical acts do not effect change (because they might do so eventually) but because I believe in earnest that hope for change is a dangerous self-delusion that blunts our ability to think critically. To put it in the pithiest way possible: “my friend, hope is a prison”.

I have, however, been involved in a micropolitical subversion of a kind on my final year module. The module is set up to have an assessed group presentation for 20% of the overall grade and for complex institutional and political reasons within the school, I can’t change that. As no one will be surprised to learn of a person who swears by the statement “if you want something done right, you have to do it yourself,” I greatly disliked group projects as a student. As an educator, I absolutely loathe them, not just for the predictable reason of resenting having to deal with the emotional labour that accompanies groupwork drama (e.g. students complaining that a member of their group has been missing meetings/not contributing equally, bickering, a group that gets stuck with the one student who has been missing lectures and so on), and not even for the ideological reason of finding business interference in the university to be morally problematic (groupwork falls into a category of things that the Business School does because it wants to give students “transferable job skills” or enhance “employability”). No, my objection is that they are not pedagogically useful, or perhaps not as useful as other methods, as students don’t learn skills that I think are important. I value mastery of a body of academic literature, critical or radically subversive thinking, extensive independent reading, and a group presentation doesn’t facilitate this. To be sure, students might learn about teamworking and interpersonal skills but a) if my life is in any way indicative, such skills are largely optional and b) me trying to impart or facilitate the development of such skills is the best example of the blind leading the blind that I can think of.

So here’s what I ended up doing: I tasked the groups to give a largely token 10 minute presentation that showcased a basic understanding of the topic and then made them sit down and earn the rest of their marks by leading a discussion of an academic journal article during which I kept interrupting, asking questions, requesting clarification, offering provocation, providing context that I didn’t think that it would be reasonable to expect them to know and so on. While I originally intended these “presentations” to be discussions that involved the entire class, in practice the sessions quickly devolved or evolved into the presenters having a four-on-one discussion with me about the paper that they’d chosen to present. A firing squad analogy would not be inappropriate, though I tried to keep things more pedagogical and collegiate. A close textual analysis of the kind that the “presentation” was designed to encourage has become all too rare in certain parts of the contemporary university, particularly the Business School, where we are often content to read the abstract, findings and conclusion of a paper to get the gist of it so that we can cite it. Indeed, many of us are content to look at no more than the paper’s the key words so that we can correctly drop it tactically into a paragraph of circle-jerking and tactical referencing. I wanted my students to be capable of more than that.

Reflecting on the sessions, many of the students rose to the challenge and held their own. I was genuinely impressed that some of them were able to not only answer my questions, but fire back interesting questions of their own. While I confess that the weaker students struggled and if a group didn’t have at least one strong student who could carry the conversation, then the hour was quite painful, but through all of this I realized that I could subvert the mores of assessment at the school because presentations aren’t subject to moderation. I gave grades based on what I thought was valuable, not what was on someone else’s marking criteria. The student’s seemed to enjoy it and valued that I clearly and honestly told them what I wanted. Reflecting on the past few months, there are many such small subversions that I am tempted to be proud of, even if they fair to challenge the conditions of the contemporary university.

Silence

The most stark juxtaposition that I experienced in the last few months has, of course been lecturing to a room of perhaps 250 students (it should be 450, but you can’t make people attend lectures) on a Monday afternoon and then spending all day Tuesday in silence because I didn’t have any classes. This was also possible because I moved to a different building this year which meant that I rarely saw anyone from my department. This juxtaposition reached its peak in my working week on a Thursday where I would have to teach Introduction to Management seminars, then have to go to my two hour Employment Relations lecture, then had to do two hours on Contemporary Management Challenges all before going to my Scout meeting where I somehow managed to volunteer to take lead on the Astronomy and Astronautics badges this term (50+ loud pre-teens are as much of a challenge as 250 undergraduates). It might not seem like much, but for me it was a lot of talking, juxtaposed against the fact that I’d then spend Friday to Sunday in silence, mostly reading and trying to prepare for the next week’s worth of lectures, without time to do much else. I ended up getting into a routine of doing vocal exercises on Monday mornings to make sure that my voice didn’t have that raspy quality of disuse for the first classes of the new week.

Particularly in January, once I got into the classroom it was almost as though I was trying to make up for the silences by filling every second with speaking. I recognize in retrospect that this was an artifacting of my own insecurity – me trying to make sure that I covered all of the content so that students would be able to do well on their exams. As the term wore on, I became more comfortable with the silences in the lecture theatre and was able to pause and think or let a point sit for a while so that it could have impact. This didn’t make the silences in my office any less of a juxtaposition, it just meant that I got used to all of them.

Scepticism

“This is where we like to talk about brain usage.” This humorous refrain became a core part of my pedagogic practice on my Introduction to Management course. I know that it’s patronizing and frankly derogatory to all of the other modules that students on that course are taking (because it implies that they aren’t using or don’t have to use their brains elsewhere), but to me it was important to keep saying it and much to my delight students started doing it by the end of the course.

A real Introduction to Management lecture slide.

For me “brain usage” is one of the key things that students can learn from me, and me in particular. There are so many morally bankrupt things that are taught or thought in the contemporary Business School that just a little bit of “brain usage” might undermine. My students take courses on “Ethical Business” that tell them that they should be ethical, not because contemporary capitalism is currently doing irreparable damage to the planet or because it consistently exploits and disadvantages the most vulnerable members of our society, but because being “ethical” is profitable. My students sincerely believe that organizations view “people as their greatest asset”, even in the context of #MeToo and increasing attention to long hours culture (as in 996) or that “transformational leaders” are the sole cause of organizational success. This is the true terror of contemporary capitalism, not pollution or exploitation, in its focus on profitability-at-any-cost it quashes all other forms of value, and subordinates all reason to economic imperatives to the point the point where “reality” becomes an exaggerated fiction of itself. I like to believe that I did something to undermine that over the course of that module, but perhaps I am deluding myself.

Self-destruction

The fourth “S” that I was going to add to this entry was going to be “success” because the feedback from my students about the last term has been quite positive (i.e. at least all of my hard-work has been worth it). Indeed, I was particularly moved by one student’s comments, and I hope that they can forgive me for the hubris of reproducing them here:

I would like to take this opportunity to explain my journey on this module. Firstly, it is no coincidence that for the second year running that Sideeq’s module has been by far and away the most enjoyable/rewarding that I have experienced this year. I started the module apprehensive about the difficulty in which I went to see Sideeq with the mindset that I may be ‘out of my depth’. However, thankfully after seeing Sideeq I left with the mindset that I can do it and feel that I haven’t looked back since and for that I can’t thank Sideeq enough. I have been aware throughout the course that Sideeq’s door has been open in which I have utilised and enjoyed some in depth discussions regarding the course. I think the best compliment that I can pay Sideeq is that he is a lecturer that is clearly passionate about the courses he teaches which I feel has rubbed off on me, keeping me intrigued throughout as well as fully engaged. Whilst I come to an end of my 3rd year studies at the university and reflecting back, I can’t help but think of how different my overall university grade will be if I had access to the same standard of teaching throughout the 3 years, showing how much of credit he is to this university.

These are deeply stirring comments, and I am exceptionally grateful to the student who gave them and am very glad to have had the opportunity to make someone’s time at university better. However, I don’t quite feel successful, I feel exhausted and the “victory” here is pyrrhic. When the term ended, I spent a few days mostly lying in bed and trying to do nothing (surprising no one, I ended up reading) because I was too tired to think about doing anything else. Perhaps the last “s” should have been “Stupidity” to reflect how moronic it was to accept the job of teaching three new modules in the same semester. Indeed, the ultimate hypocrisy of the last few months has been lecturing on the way that organizations cultivate workaholic behaviours and long-hours culture while working 70-80 hours a week or speaking about the importance of having some kind of work-life balance and not allowing oneself to be amenable to corporate control while not having any work-life balance and being exactly that. If I was being charitable, however, I might suggest that“stupidity” might refer to me actually having fun on some of my modules, the following is a real slide from a lecture where I was giving essay writing advice and was accompanied by the line “Look how sad he is, that’s how your bad introductions make my heart feel,” but if stupidity is the right word then I would argue that this is a positive and healthy form of stupidity.

Another very real lecture slide that demonstrates that I might be an idiot.

I’m not ashamed, however, to admit that there were less positive and more self-destructive forms of stupidity at work: it took quite a scotch, sleeplessness, and nicotine to get me through the last few months. The isolation and the silence also took their own tolls that I am still trying to make sense of. A certain degree of self-destruction is perhaps also healthy, to quote Deleuze and Guattari in A Thousand Plateaus:

“What does it mean to disarticulate, to cease to be an organism? How can we convey how easy it is, and the extent to which we do it every day? And how necessary caution is, the art of dosages, since overdose is a danger. You don’t do it with a sledgehammer, you use a very fine file. You invent self-destructions that have nothing to do with the death drive. Dismantling the organism has never meant killing yourself, but rather opening the body to connections that presuppose an entire assemblage, circuits, conjunctions, levels and thresholds, passages and distributions of intensity, and territories and deterritorializations measured with the craft of a surveyor” (p.159- 160)

I definitely destroyed too much of it over the last few months. Too much, too fast. I’d like to say that I’ve learned and that I won’t do it again, but I know myself better than that.

However, the last few months have been self-destructive in other ways. In a number of recent conversations with more established academics I’ve been given instructions to the tune of “Play the game”, “Be a good boy and don’t rock the boat”, “Toe/walk the line”, “You have to conform to expectations”, “This is just how things are, you can’t be so critical all the time”. And the last potential “S” thus becomes “shame” because to my own embarrassment I’ve actually started to heed this advice, not even in the sense of looking for opportunities to “play the game” and advance my career, consolidate my position, accrue power, etc. but often in the sense of keeping my mouth shut and not causing trouble (e.g. not mass emailing a paper critiquing accreditation-obsession to other members of staff while the school was recently obsessed with getting a prestigious accreditation). Drawing on it’s feminist legacy, I’ve always seen being a critical management scholar as being implicated in a politics of “causing trouble”, and it is curious to me that I feel the need to keep causing trouble. Perhaps, as I often do, I am overthinking this but I often think that if more people over-thought their actions, the world would be a better place.

Alas that most of us, to quote the eminent Thomas Harris, “can only learn so much and live.”

During the conference, I followed the stream titled

During the conference, I followed the stream titled