I’ve been listening to an alarming amount of Lo-fi hip hop, or “Chillhop” as some prefer to call it, in recent months.

The first time that I encountered “Lofi Hip Hop Radio 24/7 🎧 Chill Gaming / Study Beats” it was a Youtube stream that had a short clip of Hana, the protagonist of the inimitable Wolf Children, studying late into the night while dropping off to sleep. It is impossible for me to say exactly when I stumbled across it, but I can say which some degree of certainty how. I got into Chillhop though Nujabes, one of its great pioneers. Specifically I fell in love with the eclectic and captivating soundtrack that he designed for the exceptional anime Samurai Champloo (it is at this point that I fear that I have outed myself as a closet weeb) and then branched into his three main albums, Metaphorical Music, Spiritual State, and Modal Soul which in particular has occupied a special place in my playlists because of the ineffable affective quality of songs like “Feather” and “Reflection Eternal”.

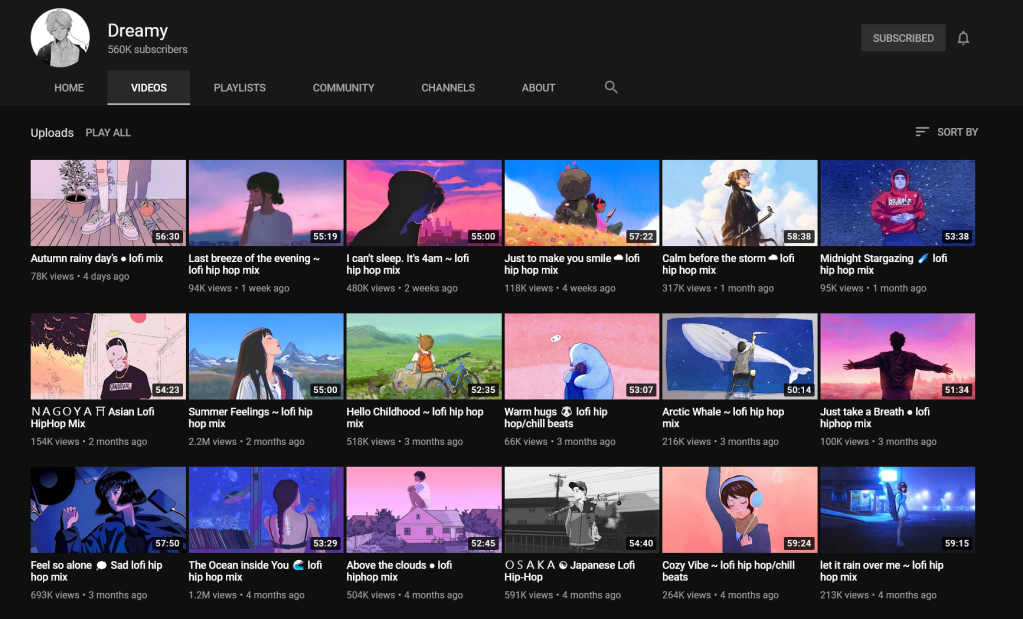

Nujabes, and many of the best Lo-fi hip hop/Chillhop artists at the moment like j’san, Kupla, Aso, j^p^n, and also artists who fall slightly outside it in the trip hop genre, like Saltillo, Halou, Bonobo, Doctor Flake, and Neat Beats, are designers of affective aesthetic soundscapes, stitching and weaving together samples and pulling life out of contemporary recording and mixing software. Their craft lies in gesturing at a particularly difficult to quantify feeling, a kind of haunting nostalgia, like something is missing or has become absent, but one is not quite aware of what one has lost, how or when this loss occurred, or why this feeling seems to be so prevalent. The affect of the genre is one that discourages what some might call “presence”. It is designed to fade into the background, to colour a setting and give it some thing like a texture rather than to shape the lines of the experience in which one is embroiled. Saltillo’s A Hair on the Head of John the Baptist does this for me better than perhaps any other piece of music, draping Hamlet quotes over haunting violins and gloomy piano lines, the song is a collage of that very peculiar feeling of absence that is so prevalent in the genre. The Youtube channel Dreamy is currently one of the better compilers of music with such sensibilities, gesturing at them ineptly with compilation titles like “I can’t sleep. It’s 4am” or “Breathing dreams like air” – a signalling of a feeling that commits you to listening but once committed, there is a kind of tragedy in the realization that there is never going to be any kind of relief or climax of that feeling, one is simply suspended there indefinitely because it is on that unironically postmodern sense that something is missing that Chillhop trades.

Speaking about Burial, and to some extent the genre of Jungle music in general, Mark Fisher once argued that through its samples and rhythms the songs spoke to a kind of nostalgia for derelict and left-behind spaces of the UK rave scene, a wistful longing for something that the artist had never experienced, a mourning for something that had disappeared like the public spaces that characterized some version of modernity, and perhaps even a kind of sentimental reminiscence for the sounds of the industrialized factory – for the pulsing, grinding, crunching, and colliding that people lived and worked under for such a long time. It strikes me that Chillhop’s explosion across contemporary platforms like Youtube and Spotify speaks to something that we all want to hear in the now, a music that colours and textures the background of whatever it is that we’re doing (whether you’re at work with your headphones in or looking longingly out the window of a lengthy train journey) but doesn’t intrude or call attention to itself. It doesn’t demand anything from you, it simply shades the silence of the room. Indeed, for some, this is exactly what it is supposed to do. As Liz Pelly writes for the Baffler

“Spotify loves “chill” playlists: they’re the purest distillation of its ambition to turn all music into emotional wallpaper. They’re also tied to what its algorithm manipulates best: mood and affect.”

While trying to keep up with the frankly absurd number of things that I am trying to do this term, I have had their music running in the background, filling my ears with a kind of nostalgia and evocation. Chillhop might be the music for the present moment, one where we are not present at all, but rather are in some ways dissociated and schizoid while still being in some sense “productive”, in transit, reading, replying to emails and so on. It’s an experience of absence, a yearning for something(?), but one isn’t quite sure what and one listens always with a half ear that some artificial intelligence or algorithm of some kind might have produced this feeling to resonate with something specific to your experience with talented multi-instrumentalists as its puppets, a mass-produced affect just for you.

I’ve written about affect on this blog before, and it remains one of the concepts in Deleuze’s work that I am not quite sure that I fully understand. I recently re-read a paper by Simon O’ Sullivan that I think explains it well, by commenting that

“affects can be described as extradiscursive and extra-textual. Affects are moments of intensity, a reaction in/on the body at the level of matter. We might even say that affects are immanent to matter. They are certainly immanent to experience […] by asking the question ‘what is an affect?’ we are already presupposing that there is an answer (an answer which must be given in language). We have in fact placed the affect in a conceptual opposition that always and everywhere promises and then frustrates meaning.) So much for writing, and for art as a kind of writing. In fact the affect is something else entirely: precisely an event or happening. Indeed, this is what defines the affect.”

An event. A happening. Perhaps my reading here is still stilted, but I see the affective as a kind of excess to the event. Something always capable of deterritorializing an experience, transmogrifying the body through the ecstasy of sensation. Yet how do we make sense of the affect of Chillhop whose affect seems to be absence, something(?) undefined that one believes is missing. The issue here is one of disentanglement. Trying to find out whether it is Chillhop that produces the affect of absence or whether the current socio-cultural milieu – from the anthropocene and our inextricably technologically-mediated lives to what Fisher called the “slow cancellation of the future” and the stagnation of popular culture coupled with the decay of all forms of human sociality that characterizes the market-centric logics of neoliberalism – is what produces this unidentifiable nostalgia for something, anything other than this.

Yet even if I am suspicious of Chillhop, and all of the comparable genres that Spotify keeps throwing at me, I won’t deny being affected by it. Indeed, even if I know that Spotify has quite likely identified me as someone who would like melancholic, nostalgic gesturing and not say, the upbeat and jubilant chill/trip hop of someone like Brock Berrigan, it doesn’t change how the music makes me feel. For example, in order to close their sophomore album, Sleep Cycles, trip-hop artist Neat Beats includes the following quote from Robert Oppenheimer in their song The Destroyer of Worlds:

“We knew the world would not be the same. A few people laughed, a few people cried. Most people were silent. I remembered the line from the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad Gita: Vishnu is trying to persuade the Prince that he should do his duty and, to impress him, takes on his multi-armed form and says, ‘Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.’ I suppose we all thought that, one way or another.”

Frisson. Every time is the first time. The slow and melancholic repeating piano loop gives me chills that make my hair stand on end and reverberate as though each were reaching out to affirm something(?) about my experience in the present but at the same time it is a kind of absent-affect, a benign and defanged background melancholia. Neither debilitating nor affirming. It is simply there, a colour in the background of my life, a partial connection, a fragment of an experience that reminds me that I am also a fragment of a thinking thing, a texturing to the office in which I spend most of my time.