So 2019 is over and one of the most noteworthy things happening in the last month was the UK’s general election. While I’m far from a politics scholar and so won’t offer any stats or breakdowns of different voting demographics, the election results resonated very strongly with two things that I’m interested in thinking about at the moment and so (as an ongoing research log) I wanted to take the opportunity to pen my thoughts on them.

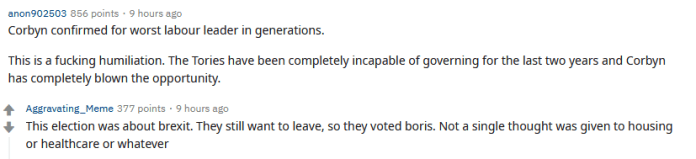

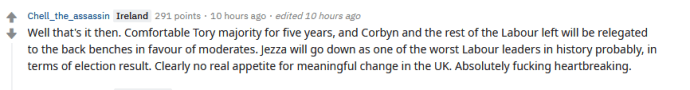

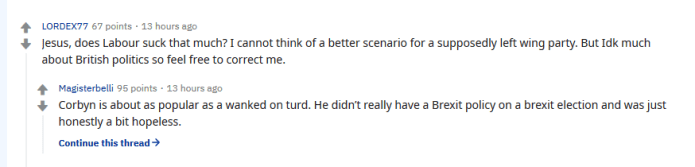

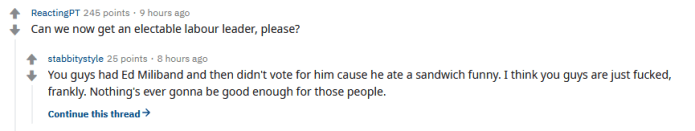

The first thing that came to my mind when the reactions to Labour’s defeat came pouring in was a clear aperception of a muffled voice crying “Ermahgerd muh leadersherp!!1!!” – thus further evidencing that I am an idiot who spends too much time on the internet. It was with a complete lack of surprise that I watched people articulate a sense of frustration and upset, targeted at Labour’s leader Jeremy Corbyn. The ire and frustration directed at Corbyn and solely at Corbyn resonated with a critique of our over-emphasis on the figure of “the leader” that I’ve been articulating in my classroom for some time. I have a guilty pleasure love of Reddit reaction threads to big events (elections, disasters etc.) and here are some of my favourite comments:

Unelectable. Worst leader in generations. With this much vitriol being thrown his way, you’d think that Corbyn had personally visited each home in Britain to insult and demean the public, not benignly offered socialism. Corbyn’s decision to refrain from giving a clear stance on Brexit was also the cause of much ire (things on Twitter were mostly the same).

The Guardian was also filled with opinion pieces, with everyone suddenly realizing that a socialist leader in an era where the Left as a whole has been losing ground across Europe was a problem. Even Polly Toynbee chimed in by suggesting that while the manifestos were magnificent, it was Jeremy Corbyn himself who caused the terrible election result and in the process “did this country profound, nation-splitting, irreparable harm”. Let’s set aside that this is a circuitous admission that electoral politics is purely a popularity contest – nothing to do with ideas or ideology, simply whether you’re the most likeable kid in the playground – because this is one of those thoughts that you’re not supposed to say out loud. Indeed, I staved that thought off when Richard Burgon was claiming: “People on the doorstep weren’t complaining about our policies, and we wouldn’t have had the policies … if it weren’t for Jeremy’s leadership.” My (admittedly juvenile) reaction to this line of argument is to simply hear someone yelling “Eomergard muh leorderhshop!!!1!”

To me, all of these post-election ‘hot takes’ are reductive. To unironically quote the smartest person that I know: “thinking about which leaders are to blame and who should be scapegoated is wholly inadequate to apprehending the complexity of the social and political problems which Brexit reflects and of which it is the product”. Indeed, a shifting patchwork of proper names who accrue blame for Brexit and the current state of British politics, with JEREMY CORBYN emblazoned at the centre, is never going to be adequate to a full analysis that disentangles the complexities of the social, political, economic, and historic factors that produce something like a Brexit-focused election. But this is not something that many are willing to think about. That a problem may be unintelligible does not gel with our sensibilities. Instead we are more interested in trying to “find the right great leader”. Of course we don’t need to work all levels to undo the ideological overwriting of the class consciousness that was naturally allied to the Left through trade unions. No we need a phenomenal leader to stand behind. Only when this “Great Man” (for it is of course gender coded) or messiah comes can the Left be saved.

I was flabbergasted when George Monbiot suggested that it wasn’t Labour leadership but rather our collective immersion in social media where ‘truth’ has become unquestionably plastic and the collective agendas of the press controlled by the wealthy. A scandalous idea. What do you mean it wasn’t Daddy’s fault; I thought that I was supposed to show how grown up I am by crucifying Daddy? To be fair, Monbiot defers blame to ‘the oligarchs’ (i.e. not one leader but a few shadowy nebulous wealthier leaders), but still, progress of a kind.

If I was a betting man, I would guess that Labour is going to adopt the ill-fated strategy of focusing their critique solely on Boris Johnson, and his name will be their catchphrase for the next few years being as synonymous with everything that is wrong with British politics as “Trump” is for the US. And thus the overestimation of the potency and powers of leaders will go on and we will continue to use them as little more than unfortunate figureheads for collective successes and failures.

What if nothing changes? #Accelerate

Recently I’ve been getting back into the work of Nick Land, a fringe figure in Deleuze Studies. For a time in the 1990’s, Land was producing some of the most insightful and creative Deleuzian work in the English speaking world. The essays in Fanged Noumena – which I’m still slowing making my way through – are some of the most innovative in terms of developing Deleuze’s style of thinking and writing; a mad production and proliferation of concepts. Drawing on many of Land’s ideas, particularly his writings on capital, a number of critical scholars and philosophers, disenchanted and disillusioned with continuously failing modes and practices of resistance to the capitalist mode of production and enchanted by the trajectory and speed of technological progress, have begun to advance what has been described as Accelerationism, a belief that the best mode of resistance is an acceleration of capitalism’s dynamics. In their introduction to #Accelerate: The Accelerationist Reader, Mackay and Avanessian (2014, p. 4) define Accelerationism as

‘the insistence that the only radical political response to capitalism is not to protest, disrupt, or critique, nor to await its demise at the hands of its own contradictions, but to accelerate its uprooting, alienating, decoding and abstractive tendencies.’

Drawing on the works of academic luminaries like Mark Fisher and other authors who find their inspiration in the Marxist traditions of Lyotard or Deleuze and Guattari, Accelerationism tells a rather bleak story that suggests that modes of resisting capitalist capture are futile, that capitalism cannot be ‘greened’, reformed, made to be benevolent, or made to serve broader social interests through the striking of a Faustian ‘new deals’. Rather, the most meaningful mode of resistance left is to accelerate capitalism’s destructive tendencies and see what comes next.

Many Accelerationists are fond of quoting the following passage from Anti-Oedipus, which obviously signposts my interest in it:

‘What is the solution? Which is the revolutionary path? […] Is there one? – To withdraw […] Or might it be to go in the opposite direction? To go still further, that is, in the movement of the market, of decoding and deterritorialization? For perhaps the flows are not yet deterritorialized enough, not decoded enough […] Not to withdraw from the process, but to go further, to “accelerate the process,” as Nietzsche put it: in this matter, the truth is that we haven’t seen anything yet.’ (Deleuze & Guattari, 2000, pp. 239–240)

That is to say, perhaps the way to resist capitalism is to push it to its limits, to pursue fully the logic of decoding or the axiomatic of extracting surplus value until they arrive at their most extreme conclusion, all surplus value extracted, all growth targets achieved, all possible labour rendered, the planet Earth reimagined as an uncommodifiable and unliveable plane. The Accelerationist position revels in the idea that we might seek to encourage capitalistic destruction as a mode of revolution and envisions various techno-futurist dystopias in which this might be possible.

There are certain aspects of Accelerationism that I don’t agree with. For example, I agree with what I read as Viveiros de Castro’s objection to its Prometheanism, and I’m more than a little uncomfortable with the turn to neoreactionarism that is a part of Nick Land’s later work. It also seems to me that many misinterpret Land’s essay Making it with Death: Remarks on Thanatos and Desiring-Production when he speaks about the potential limits of capital.

“All of which is to raise the issue of the notorious “death of capitalism”, which has been predominantly treated as a matter of either dread or hope, scepticism or belief. Capital, one is told, will either survive, or not. Such projective eschatology completely misses the point, which is that death is not an extrinsic possibility of capital, but an inherent function. The death of capital is less a prophecy than a machine part.” (Land, 1993, p. 68)

Because to me this speaks less to the need to accelerate to catalyse the death of capital and more to the impossibility of there being any outside to capital. Capital will sell us the possibility of its death when that becomes the means by which to achieve its ends. Is this not the best explanation for “corporate environmentalism”? This is something that I’ve been thinking about often over the last few months. I raise it here because it made me reflect on the election results. The political Left in the UK now seems to me to occupy a position that is best described as “accidentally accelerationist”.

I make no secret of my love for Thomas Harris, and one of his most eminently quotable passages is the following in Hannibal: “There is a common emotion we all recognize and have not yet named—the happy anticipation of being able to feel contempt.” The happy anticipation of being about to feel contempt. The Left seems to be currently actively expecting and verging on actively willing our society to collapse, for all to come to ruin so that it could say “I told you so”. See peasants, I told you to vote for Corbyn. Now the NHS is privatised, firms have taken their business to Europe, the gaps between rich and poor have increased and austerity is still ongoing. I told you so. Which is to say that the Left is currently hoping that some part of Accelerationism is true, that the tendencies of capital to privatize rather than seek public interest, to agglomerate private wealth, to consistently make the poorest and most vulnerable worse off, to exploit natural resources for its gains, spurs some kind of societal or ecological collapse.

The worst case scenario for the political Left is that nothing bad happens. We see that the Tories have already committed to raising the minimum wage. If the NHS doesn’t fall apart, if there isn’t mass unemployment, if Brexit doesn’t wreck the economy, if there isn’t mass homelessness, or spikes in violent crime etc. etc. then it is likely that those long-standing Labour seats that turned blue in December will stay blue with more to come and we will not see a Labour government again in my lifetime.

This to me is as interesting as it is perverse. Of course, most politicians are simply bureaucratic functionaries, bumbling along and doing what they think is in the best interest of the country. However it intrigues me, in a way that makes me reflect on the appeal of “Leadership”, to think about a Malcolm Tucker-esque figure, sitting in Labour HQ right now, realizing that the best political strategy may not be resistance but acquiescence. “At thy choice, then […] Come all to ruin.”