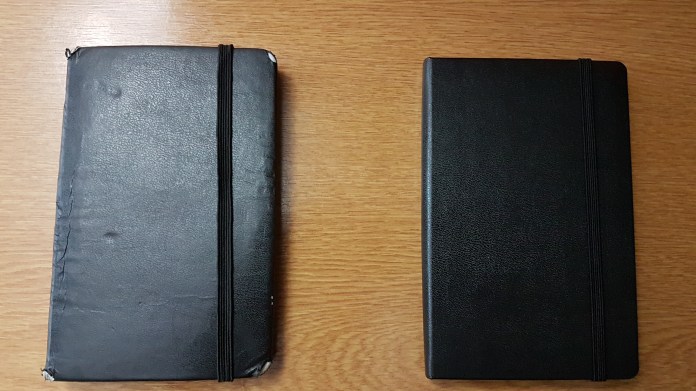

Anyone who knows me will recognize the notebook pictured above because I’ve been carrying ones like them around since 2012. They can usually be found sticking out of my back pocket or placed almost defensively on the table between me and the person to whom I am speaking in what I imagine must be the most curiously threatening non-threatening gesture: “Be interesting or I’ll start reading something that is.”

Anyone who knows me will recognize the notebook pictured above because I’ve been carrying ones like them around since 2012. They can usually be found sticking out of my back pocket or placed almost defensively on the table between me and the person to whom I am speaking in what I imagine must be the most curiously threatening non-threatening gesture: “Be interesting or I’ll start reading something that is.”

I started a new notebook recently. While the corporeality of a new notebook is both a gift and a curse (the enticing song of fresh pages turning versus the annoying sensation of sitting on a book that has not yet adapted to match the contour of my arse), in thumbing through the old notebook in a kind of farewell gesture I came across a number of fragments of ideas. These partial jottings, questions posed to no one but my future self, scribbled random thoughts and etcetera are of great interest to me because they always reflect an intellectual space that I previously occupied which is now irrecoverable. All that is left is the writing, what Artaud might see as the waste parts of the thinking and the self that did the inscription.

A few of these notes are short and stood out because of various things that I’m working on or thinking about at the moment. For example, the following note, which I wrote from a place of great frustration as I tried to write a paper explaining the heterogeneity of concepts.

“We already know that concepts are heterogeneous”

She says “I love you. “I love you too,” you reply. Neither of you mean the same thing.

When I explain why I chose to study Deleuze and Guattari for my PhD and why I’m still so fascinated by their work, it is concepts that I end up placing the most emphasis on and being most interested in. The concepts that we use to think are always moving and shifting around us. Nothing has any kind of fixity. Concepts are always changing, growing, and evolving. We already know this as it is an intrinsic quality of our language and our experience but it is often easier to pretend that we do not know, that the things that we say or the concepts that we use to think have a kind of permanence that lasts beyond the act of saying them. For Deleuze, this is a reflection of our collective entrenchment in the metaphysics of identity, a mode of thinking that privileges stable states and being over change and becomings. This is difficult to explain to people without a background in philosophy, so I am always looking for simple examples that get the point across.

Some notes, however, prompted longer reflections and I decided that one was also important enough to include here. For example: “You wouldn’t know a dystopia if you were living in it. Indeed, ours is the most boring dystopia possible.”

If you were living in a nightmarish and totalitarian dystopia, would you know? I wrote this question down with no context and can’t even recollect exactly what I was thinking about when I wrote it. I speculate that it may have been related to the fact that I recently binged the exceptional Amazon series The Boys. While my “nerd credentials” are severely lacking when it comes to comic-book fandom, I have always greatly enjoyed the proceeds of the dark deconstructions of the superhero genre like those of Alan Moore or Frank Miller (e.g. Watchmen or The Dark Knight). While I might be underqualified to make such an observation, The Boys seems to follow in their tradition. What interests me in particular about The Boys is that – at least in its filmed incarnation – it seems dystopian only because we see it through the lens of the directorial gaze which shows us the dysfunctions of the Supers as well as the corrupt and manipulative nature of the corporation, Vought International, which employs them for its own revenue maximization – embracing all of the most gross tropes of the society of spectacle in order to profit off of the value of the superheroes under their employ.

The character of Homelander particularly interested me as he functions as a critical reflection on what an impossibly strong, fast, and unkillable being would be like if it walked among us. Gone is the image of the benevolent image of the Superman as a messianic saviour, now Superman is a brutal tyrant who decides with absolute freedom who can live and who should die.

I reflected that what Homelander renders salient is the reason that I enjoyed the Snyder/Nolan take on Superman in Man of Steel. Christopher Reeve’s Superman was inherently a symbol of unwavering hope, whereas Henry Cavill’s explores the question of whether it is possible to be hopeful at all in a world that seems to offer nothing about which one could be hopeful. Its message is that there is no good in the world unless you make it for yourself; there is only loneliness and isolation. The film seems to propose that to maintain ones status as a shining beacon of hope in such a world is the act of a super-man, someone beyond human. To choose to be good when it would be so much easier, or so much more fun, to stamp out a human life like it were that of an unwelcome insect, is what it means to be an inspiration in the present. This is something that I (however problematically) try to explain to my students, virtue is not virtue when it is convenient or when being virtuous is your most profitable option. However, movie critics whose opinions I respect didn’t enjoy Man of Steel and in retrospect deemed it disappointing.

Back to The Boys. What I enjoyed about the show in the same way that I enjoyed Black Mirror and Hannibal, is that reflective of the contemporary milieu, it explores the dark, the horrible, the uncomfortable, the unwelcome. Characters are sexually assaulted/coerced, superheroes are murderers who cannot be stopped, overpowered, or harmed, characters die meaningless deaths, unfettered capitalism leads to the privatization of policing and then national defence. We enjoy watching this as it shows us not a fantasy, but rather, it renders salient a particular dynamic that we wish we could see within the present where there are evil men who do not die, who kill with impunity, profit off of the insecurity of others, and stand above the law – the unsettling ambiguity of contemporary life means that none of these things are easily observable and when they are, the feel like cheap spectacle.

Indeed, the show is at its most subversive where it gives us glimpses of a reality where everyday life looks almost exactly like ours. We follow “The Boys” in their fight against the Supers and we see how their quest is justified by the Supers’ brutality, but what we do not see is how life must be for the millions of people who are not victims of and have no reason to hate the Supers. They’re pretty happy watching the spectacle of a races, films, buying merchandise, and seeing criminals torn to shreds on the news. The little snippets that we see are deliberately evocative of contemporary superhero culture – in order to see it, one need only imagine that the characters in the Marvel movies were real and that we’d received the films in the same way, created the same fandoms, had their posters on our walls, and tucked ourselves into bed under Captain America duvets, all while the good Captain spent his private life enjoying kicking orphaned refugee children to death.

In this sense, we might reflect that we live in the most boring possible dystopia. There aren’t even jackbooted, masked fascists kicking ethnic minorities on my street corner. There is only a casual acceptance of state surveillance, death from overwork, hero-worship of leaders and politicians, and exploitation and mass ecological destruction carried out by corporations for profits, in ways that are too unclear to point to or hold to account. Much like the background characters in The Boys, we wouldn’t know that we were in someone’s dystopian nightmare and would likely ignore the realization if we were told. It’s easier to keep believing that everything is ok.

This reminds me of something that Werner Herzog said, regarding the fact that he encouraged a colleague to watch Wrestlemania: “You must not avert your eyes. This what is coming at us.” Herzog is suggesting that if a collective, anonymous body of us wants to see this empty spectacle of sweaty, oiled up male bodies contorting and writhing, then the poet, the filmmaker, the artist, the critic, must not look away. It’s hard to keep looking when things are bleak. I wonder if there is not an abdication of the pessimistic ethics of hopelessness. A resignation to continue to live even as things are not getting better and indeed, to live with the negative visualization that begins from the assumption that things will not get better. Nietzsche’s old quip about gazing into the void is here poignant because of its relevance. One cannot continue to stare; it takes a psychological toll. Indeed, the more that I read of Mark Fisher’s work, for example, the more that I wonder whether he looked too long at the existential void of capitalist realism. Even Accelerationism doesn’t offer much hope and it may indeed be difficult for many to live without it. However, I wonder if we do not have a responsibility to continue to look. To see and feel all of the social’s miscellaneous effects, to not avert our eyes as Herzog suggests. In order to diagnose, critique, and make sense of the culture, you must, for Herzog continue to look at what is happening and see the dystopian. What this tells us about The Boys is something simple, we are currently living through a time that is so disparaging that it makes more sense to us to kill our gods than to believe that they still care about us. We are too reflexively cynical to allow ourselves to believe in kindly Superman, saving a kitten stuck in a tree, and instead find it easier to believe that the super-man is a brutal, self-centred, rapist who lives entirely in the service of capital. The latter is perhaps not only a more believable story, based on the stories that we see and hear every day, but it is the one that we want to be true as it also serves to render intelligible the reality in which we find ourselves – helping us feel that we understand what is taking place. We must keep looking at the social, political, and technical forces that produce a society unwilling to believe in a wholly and perfectly good superman.

What Herzog’s injunction means for the wider society in which we live, however, is more troubling. We need to keep thinking about the anonymous collective body whose desire is interested in the production of misery, of inequality, of suffering, as a spectacle that it can watch. So called instances of poverty porn, or films that feature the manipulative manager – are they acts of subversion and truth telling, or attempts to provide clear individuals for us to be outraged at and ignore broader systematic and structural issues.

Pingback: There is no Outside: Notes on Capital’s self-awareness | Sideeq Mohammed